Перекрёстные ссылки книги для 2. Administrative controls

Administrative controls are interventions aimed at reducing exposure and thus the transmission of M. tuberculosis in health facilities and congregate settings. These controls include triage to identify people with presumptive TB and then separate them, prompt evaluation for TB, initiation of effective TB treatment, and access to tools for respiratory protection. Implementation of administrative controls involves the development of institutional policies, protocols, education and oversight aimed at establishing mechanisms for reducing exposure to and transmission of TB within the facility (20). Actions to consider as part of administrative controls include the following:

- assign responsibility for TB IPC to a specific person within the facility IPC committee;

- conduct a TB transmission risk assessment at the facility;

- develop a written TB IPC plan;

- train and educate all staff and volunteers on TB IPC;

- educate patients and visitors at the health care facility about TB IPC;

- display appropriate signage and promote respiratory hygiene throughout the facility;

- separate coughing patients from others in waiting areas;

- fast-track coughing patients through care, and minimize the time they spend in the health facility;

- provide coughing patients with medical masks;

- establish a system for baseline and periodic TB screening and evaluation of staff based on their risk of TB exposure, and provide free TB treatment and TB preventive treatment (TPT);

- implement protocols for triage and airborne precautions following epidemiological principles,applying criteria for isolation or separation of patients with presumptive and infectious TB;

- ensure proper cleaning, sterilization or disinfection of equipment (particularly equipment used during procedures such as sputum induction, bronchoscopy, anaesthesia or surgery);

- ensure access to rapid molecular testing for people with presumptive TB;

- promptly start effective TB treatment based on drug-susceptibility testing (DST) results when TB is confirmed and ensure support for people to adhere to treatment as prescribed;

- implement organizational measures to ensure effective and sustainable use of environmental controls and personal respiratory protection;

- facilitate collection and review of TB data by the IPC committee; and

- ensure that all individuals identified as having TB are notified and that appropriate follow-up actions are taken.

The rest of this chapter outlines mechanisms for the programmatic implementation of these administrative control activities and thus of the package of TB IPC interventions.

2.1 Coordination and planning of TB IPC activities

2.1.1 National level

At the national level, the MoH should designate a senior officer as a focal person to coordinate the implementation of TB IPC activities. The focal person should be tasked with planning, resource mobilization, capacity-building and monitoring of the implementation of the TB IPC programme at the national level. Indicative terms of reference for the national TB IPC focal person are as follows:

- develop a national TB IPC plan and incorporate TB within the broader national IPC plan when available;

- facilitate the development and updating of relevant national norms and regulations, in accordance with the national TB IPC guidelines;

- coordinate the development and systematic dissemination of educational and advocacy material on TB IPC to all stakeholders at relevant service delivery points in the country;

- advocate for funding and resources from different ministries and donors to implement TB IPC at national and subnational levels;

- coordinate the implementation of TB IPC activities with other national programmes (e.g. for HIV, nutrition and NCDs such as diabetes mellitus) and other sectors beyond health (e.g. in congregate settings);

- facilitate the implementation of TB IPC activities through community-based organizations and private health care providers;

- facilitate the systematic recording, reporting and monitoring of the implementation of TB IPC activities through the national health management information system (HMIS) or special TB IPC surveys; and

- facilitate operational research to document best practices and experiences within the country or in specific congregate settings.

2.1.2 Subnational and facility-level IPC focal person

Systematic implementation of TB IPC at subnational and facility levels requires the availability of designated staff to coordinate it. For the implementation to be successful, the officer in charge of TB IPC needs to have the support and authority, budget and human resources to implement it (20). Support should include the authority to conduct TB risk assessments for facilities; develop regional, facility- and department-level budgeted plans; and facilitate the implementation of TB IPC policies and plans. Specific actions suggested are as follows:

- A health care worker who is employed full time, such as a nurse, must be relieved of part or all of their clinical duties, depending on the size of the institution, to ensure that adequate time is available for oversight of IPC implementation, including TB IPC. In a small clinic, one person may be sufficient for IPC; however, in a large hospital, several people will probably be needed.

- The person or people responsible for TB IPC should ideally have clinical experience, to understand the nature of transmission of M. tuberculosis and its infectivity. If an individual without any clinical background is appointed to oversee TB IPC, they must be trained in basic TB IPC (including the mechanics of M. tuberculosis transmission) and be knowledgeable about the populations most at risk of TB infection in the facility’s service areas.

- The IPC focal person or people should identify populations vulnerable to TB disease progression and ensure that they are given priority. Such populations include children and people with HIV, cancer or other immunocompromising conditions, including those caused by their medication (e.g. steroids, chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs). The IPC focal person should ensure that the recommended TB screening, training and education of health care personnel and other staff at risk are undertaken regularly.

2.1.3 IPC committee at facility level

In addition to an IPC programme leader, facilities such as hospitals and outpatient clinics serving a large population may create multidisciplinary IPC committees that bring together key members of staff. In a large facility or hospital, the committee should include a range of representatives who can advise on policy and protocols and assist with implementation. This could include representatives from facility management; the microbiology laboratory; multiple clinical disciplines (e.g. medicine, nursing, surgery and paediatrics); and the occupational health, environmental science, engineering, quality assurance and facility maintenance departments. The key to effective IPC is to motivate staff, In addition to an IPC programme leader, facilities such as hospitals and outpatient clinics serving a large population may create multidisciplinary IPC committees that bring together key members of staff. In a large facility or hospital, the committee should include a range of representatives who can advise on policy and protocols and assist with implementation. This could include representatives from facility management; the microbiology laboratory; multiple clinical disciplines (e.g. medicine, nursing, surgery and paediatrics); and the occupational health, environmental science, engineering, quality assurance and facility maintenance departments. The key to effective IPC is to motivate staff, clients, and visitors to follow IPC procedures and policies for airborne infection control. The TB IPC focal person and the IPC committee should undertake the following actions:

- develop a TB IPC implementation plan aligned to the national IPC guidelines; the plan should include a budget to strengthen TB IPC measures, which takes into account the risk of TB transmission;

- advise facility administration on the choice of IPC tools (e.g. certified respirators, masks, germicidal ultraviolet [GUV], signage and location of waiting areas) and ventilation equipment suitable for the local context;

- liaise with relevant authorities and staff in the facility (e.g. procurement, maintenance, waste management, pharmacy and housekeeping services) to ensure that the required materials are available and that the TB IPC is implemented smoothly;

- review the status of implementation of TB IPC in the facility and identify key gaps;

- undertake assessment of risk of transmission of M. tuberculosis across the health facility, including waiting areas, consultation rooms for all health care workers, inpatient wards, pharmacy and investigation rooms (e.g. laboratory and radiology unit);

- introduce any system changes that are needed to minimize the risk of transmission of M. tuberculosis, including establishing appropriate patient flows and seating arrangements, installation of equipment and provision of PPE, as necessary;

- ensure the availability and use of SOPs and working protocols for all levels of staff;

- convene regular meetings (e.g. monthly or quarterly), assign responsibilities for implementation of TB IPC activities within the facility and designate members from the IPC committee for oversight;

- develop a schedule and mechanism for monitoring the implementation of TB IPC;

- organize initial and regular refresher training programmes for health care workers and other staff;

- organize ongoing education and capacity-building activities that are practical and participatory for facility staff, and organize education sessions for patients and visitors to the facility;

- recruit and make use of TB champions and other leaders, and ensure that signs and educational materials are displayed across the facility.

- In terms of oversight:

- undertake annual reviews to update facility SOPs and working protocols for TB IPC, in accordance with national IPC guidelines;

- establish a mechanism for routine monitoring of compliance with SOPs or working protocols by health care workers, other staff, patients and visitors to the health facility;

- establish a mechanism for routine (e.g. monthly or quarterly) review of data on TB and TB infection among health care workers and other staff, to identify high-risk settings and situations; and

- immediately investigate any outbreak of TB or drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) reported in the facility.

2.1.4 TB IPC facility risk assessment

The IPC committee and TB IPC focal person should undertake TB risk assessments of the facility. The assessment team should include knowledgeable facility staff and health care workers who are familiar with the flow of patients and functional issues (e.g. patient crowding at certain times of day; windows that do not open easily; problematic heating, ventilation or air-conditioning systems and GUV fixtures; use of medical masks; and status of fit-testing). The assessment will help to identify areas of the TB IPC programme that might benefit from change or enhancement, and it should be undertaken at least once a year. The assessment should include evaluation of the effectiveness and level of implementation of the IPC plan, and review of previous recommendations for change. Key elements that should be assessed are outlined below:

- The assessment team should review:

- patient flow at various times of day, identifying areas of overcrowding;

- seasonal increases in patient flow;

- the location and scheduling of TB services (e.g. are the services immediately adjacent to the HIV clinic or oncology clinic, with potential overflow of waiting patients?);

- high-risk areas such as congregation and waiting areas, hospital wards and the area used for sputum induction (e.g. is this outdoors or in a well-ventilated space, a booth or a negative-pressure room); and

- the implementation status of environmental controls and the respiratory protection measures used by staff and visitors

- The team should undertake additional risk assessment of:

- any ongoing construction or renovation of the facility;

- creation of any new patient waiting or treatment areas;

- implementation of new TB diagnostic and treatment guidelines; and

- availability of staff to manage the workload in the facility.

The findings from the risk assessment should be systematically documented and shared with the IPC committee for review; any recommended actions should be systematically implemented and monitored. Annex 2 provides an example of a TB risk assessment tool for a facility.

2.1.5 Facility TB IPC implementation plan

Following the risk assessment, a facility TB IPC implementation plan should be developed or updated to address identified gaps and to scale up best practices. The plan should receive input from the IPC committee, facility staff and management, to ensure that sufficient human and financial resources are allocated. The plan may include short-, medium- and long-term actions along with estimated cost. If structural changes are deemed necessary to improve TB IPC measures (e.g. measures to decrease overcrowding or improve ventilation), an engineer should also have input into the TB IPC plan. The person in charge of the facility should formally sign off on the plan to ensure accountability for implementation. In general, the TB IPC plan should include:

- basic information:

- location, basic information about the setting;

- service or services offered;

- updated TB epidemiology (at facility, state and local level; people in the community served by the facility who are at increased risk of TB; and staff);

- results of the latest TB IPC facility risk assessment and areas at potential high risk of TB;

- administrative controls:

- assignment of responsibilities for TB IPC;

- contact information of the TB IPC focal person;

- a training and education plan for staff;

- an education plan for patients, clients and visitors;

- a schedule for TB screening and evaluation of health care workers and other staff, including TB treatment and provision of TPT;

- protocols for triage and precautions against airborne infections;

- signage and support for respiratory hygiene;

- policies and protocols for communication and collaboration with local or state health departments and clinical and laboratory services;

- environmental controls:

- policies and protocols to ensure cleaning and maintenance of TB IPC equipment (e.g. GUV fixtures and mechanical ventilation systems);

- measures to improve mechanical and natural ventilation;

- measures to improve adherence to SOPs for upper-room GUV systems (including adequate air mixing);

- respiratory protection:

- a personal respiratory protection programme for at-risk employees:

- training and on-the-job education on the use of respirators;

- adequate supply of different sizes and models or brands of certified respirators for staff and care providers in the community, and for households;

- fit-testing for respirators;

- medical masks (for potential and confirmed TB patients, clients and visitors);

- a personal respiratory protection programme for at-risk employees:

- sustainable TB IPC implementation:

- identification of human resources and appropriate assignment of TB IPC responsibilities;

- mobilization and allocation of funding for implementation of TB IPC activities; and

- allocation of human and financial resources for continual quality improvement activities.

An example of a TB IPC plan developed by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) – the Basic TB infection control risk assessment tool – is included in Annex 3.

2.2 Implementation of administrative controls

2.2.1 Triage

In the context of TB IPC, triage implies a preliminary intervention to identify individuals with signs or symptoms of TB among those visiting a facility. It is used to fast-track those with signs or symptoms through the waiting areas to the facilities for clinical evaluation, TB investigation, provision of treatment, and isolation or respiratory separation, as necessary. The purpose is to minimize the time a potentially infectious individual spends in the health facility or congregate setting and thus the chance of them transmitting TB to others. Triage alone is estimated to reduce the absolute risk of incident TB infection by about 6% among health care workers in all settings (the absolute risk reduction may vary from 3% in settings with a low TB burden to 1.7% in settings with a high TB burden); among non-health care workers the risk reduction was found to be 12.6% (13).

Programmatic implementation of triage requires the following steps for identification and management of individuals having presumptive or confirmed TB:

- Health care workers or community volunteers working at the health facility may be designated to assess visitors at the facility entry, or as soon as visitors are seated in the waiting area.

- The designated individuals should watch for people who cough and should use a checklist to assess whether those people are exhibiting signs or symptoms that are suggestive of TB; health care personnel need to maintain a relatively high level of vigilance for TB.

- Once identified, individuals with a cough or other signs and symptoms of TB should be separated from other visitors and fast-tracked through all queues for medical evaluation and diagnostic testing, following proper precautions for airborne infections.

- All medical staff caring for individuals who are potential TB patients should wear certified respirators (N95, filtering facepiece 2 [FFP2] or elastomeric) when in contact with patients who are or who may be infectious.

- Health care personnel or staff should educate patients and caregivers about TB transmission within the hospital and the home – care should be taken to reduce potential stigma for the patient, particularly from family or community members.

- The IPC focal person for the facility should talk to patients and visitors on a regular basis, to understand their perspectives on the way triage and fast-tracking are carried out. The focal person should aim to make the process more subtle and acceptable, to avoid stigmatization or alienation of the patients.

- Triage may sometimes be followed by respiratory separation or isolation, or the start of TB treatment if TB is confirmed.

- People living with HIV should be systematically screened for TB at each visit (21). HIV testing should be offered to all patients with presumptive and diagnosed TB, especially in settings with a high burden of HIV (22).

- Triage may also be implemented at dedicated diabetes clinics and other medical facilities where patients may be at high risk of TB. Triage at other locations with a high risk of TB transmission is also likely to be of benefit (13), particularly where those with presumed TB may congregate; for example, in long-term care facilities or correctional facilities.

Fig. 2.1 provides an illustrative example of patient flow from a health facility in Ghana, a country with a high burden of both TB and HIV (12). An example of triage implementation is presented in Box 2.1.

Key point: Consultation and continued dialogue with health care workers, patients and visitors are needed to implement TB IPC properly and avoid the worsening of stigma or the alienation of patients.

Fig. 2.1. Example of patient flow at an outpatient clinic in Ghana

Source: Implementing the WHO Policy on TB Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities, Congregate Settings and Households. (12)

Box 2.1. An illustrative example of triage in a busy antiretroviral therapy (ART) centre in a setting with a high burden of TB

The person in charge of the hospital recently entrusted a trained community volunteer with the task of identifying any individuals with a cough presenting either at the reception of the ART centre or in the waiting area. The volunteer is required to perform triage in a patientfriendly manner, without stigmatizing the individual or disrupting care for other patients. Also, the volunteer is instructed to use a medical mask at all times and to offer medical masks to individuals with signs or symptoms of TB.

Once the volunteer identifies an individual with signs or symptoms of TB, they accompany that person to the front of the queue to see the nurse or doctor. Following evaluation by the nurse or doctor, the volunteer takes the patient quickly to the head of the queue at the pharmacy to collect antiretroviral (ARV) drugs. The volunteer then hands the patient to a second volunteer, who accompanies the patient to a sputum testing centre. Once the sputum specimen has been submitted, the patient is asked to leave the health facility and to return for review of the results of the investigation, when available.

Key point: The purpose of triage is to fast-track the clinical management of patients with presumed TB, to minimize the time they spend in the facility and reduce their contact with others. Rapid testing and prompt initiation of treatment for TB patients is critical.

2.2.2 Respiratory separation or isolation

Evidence

Overall, the studies reporting on the impact of administrative control measures in TB IPC have serious limitations; for example, the studies have small estimates of effect and large variance. In the few relevant studies included in systematic reviews considered by the WHO GDG, an absolute risk reduction of 2% was noted among health care workers when individuals with presumed or confirmed TB underwent respiratory separation or isolation; however, no studies are available in other populations. In low TB burden settings, respiratory separation as a part of a package of interventions achieved a risk reduction of 12.6% for TB disease in those attending secondary- or tertiary-level health facilities (13).

Implementation of respiratory separation or isolation

Respiratory separation or isolation should be implemented as part of a package of TB IPC interventions in situations where good-quality patient care and support are offered, TB treatment is available and other measures to prevent airborne transmission are in place. The preferred approach is prompt TB treatment, health education, counselling and constant dialogue with the patient and their family. Providing treatment and support and ensuring adherence through patient-friendly and decentralized models of care, is often adequate to obtain successful outcomes and minimize transmission in health facilities. However, when these measures fail and there is a real risk that M. tuberculosis will be transmitted to the immediate family or the community, health providers or authorities may need to decide on and implement respiratory separation or isolation of the patient.

Prior to separation or isolation, individual risk assessment should be undertaken, using a human-rights-based approach that balances the potential risks and benefits to both the patient and the health care workers, and the community in general. In situations where isolation is deemed necessary, it should be implemented in consultation with the patient and their family or caregivers in a medically appropriate setting. Respiratory separation or isolation should be discontinued as soon as the infectious period has been completed. The following are examples of patients for whom respiratory separation or isolation may be required (6, 7):

- respiratory separation or inpatient care:

- a person with infectious severe pulmonary TB or DR-TB requiring hospital admission; for example, for respiratory failure or a condition requiring medical intervention (e.g. haemorrhage, pneumothorax and pleural effusion);

- a person with TB with severe comorbidities (e.g. HIV, liver disease, renal disease or uncontrolled diabetes);

- a TB patient on treatment, presenting with severe adverse events (e.g. hepatitis, psychosis, renal failure, hearing loss or arrythmias);

- isolation:

- treatment failure;

- infectious TB patients housed in congregate settings or long-stay health facilities;

- situations where effective and safe TB treatment cannot be ensured in an outpatient, community or home setting (e.g. people who are homeless, have chronic alcoholism, pose a risk of exposure to children aged <5 years, are immunocompromised or are pregnant); and

- nonadherence to treatment (as a last resort when other care options are exhausted).

When respiratory separation or isolation is necessary, precautions should be more stringent for individuals with bacteriologically confirmed TB and those who are immunosuppressed (e.g. HIVpositive). If patients are bacteriologically negative, they are less likely to infect others and can even be placed in general wards. Infectious TB patients should be admitted to wards with adequate TB IPC measures and adequate distance between beds. HIV-infected individuals should not share space with TB patients; in particular, the exposure of individuals with HIV to infectious TB patients should be avoided.

The use of involuntary hospitalization and incarceration of TB cases is not specifically addressed in the WHO TB IPC guidelines (13, 23). Isolation should be regarded as a last resort, when all other options have failed. Authorities and those implementing the controls need to consider patient rights, and balance individual liberties with the advancement of the common good (24). Prerequisites for programmatic implementation of isolation include:

- availability of:

- clear protocols and guidance;

- isolation rooms (i.e. spaces with or without negative-pressure ventilation and that meet minimum standards for patient care and hygiene);

- staff trained in counselling and in explaining the rationale behind isolation measures;

- adequate human and financial resources to ensure proper isolation while protecting patient rights and not increasing TB risks for health care workers or other attendants;

- clear criteria for de-isolation being available and disseminated;

- health care workers trained to undertake mental health risk assessments, identify signs and symptoms of anxiety and depression, and provide the necessary support – this is important because individuals isolated for extended periods may experience greater levels of anxiety, depression, anger or feelings of imprisonment;

- measures to minimize the risk posed by infectious patients to health care workers, other patients and visitors; for example, adequate ventilation (e.g. 12 air changes per hour [ACH] with natural ventilation), provision of respirators for health care workers and medical masks for visitors, facilities for hand washing and sanitization, and regular disinfection of floors; and

- open spaces that allow patients to socialize without the risk of transmission.

Fig. 2.2. Inpatient care ward for infectious TB patients

Source: TB and Leprosy Hospital, Damien Foundation, Shambhuganj, Bangladesh.

Policy for visitors and attendants

It is important to keep to a minimum the number of people visiting isolated patients, while still allowing some visitors or attendants for the patient’s emotional well-being and care. Patients should be educated about the cause, spread and prevention of TB infection. Also, the need for isolation or admission and for restrictions on the number of visitors should be explained. Children, pregnant women and people who are immunocompromised should not be allowed to enter isolation areas. Visitors should wear a medical mask or respirator at all times; they should not sit or lie down on the patient’s bed; and they should maintain personal hygiene through hand washing or use of alcohol hand rub before and after meeting the patient. If a patient is ambulatory and weather permits, visitors may be encouraged to meet the patient in a designated outdoor space if available.

Respiratory separation is also possible at home, in situations where patients are sputum smear positive but do not require admission or where patients have no comorbidities and not suffering from adverse events. The person may be provided a separate, well-ventilated room, given a medical mask, and told not to visit crowded places or use public transportation; in addition, household members should be trained in the basics of TB IPC.

Key point: National programmes should promote good-quality patient care and support measures to provide effective TB treatment with decentralized models of care. Isolation is usually only necessary for a brief period – typically a couple of weeks – until the patient is no longer infectious.

2.2.3 Prompt TB treatment

Evidence

A systematic review found that delay in initiation of TB treatment contributed to an extended period of infectiousness and increased the risk of ongoing TB transmission (13). Also, in settings where patients rapidly received effective TB treatment guided by DST, health care workers experienced an absolute TB risk reduction of 3.4% compared with settings where treatment was delayed. A reduction of 6.2% in TB incidence was noted among HIV-positive individuals who were admitted to health care facilities, from 8.8% to 2.6%, following the implementation of specific IPC measures (including prompt TB treatment, which also has a direct effect on survival) (13). Patients on TB treatment appear to be less infectious than patients not receiving effective TB treatment; however, data are lacking on the exact time it takes for patients to become noninfectious and there is considerable variation in the time taken to achieve bacteriological (sputum smear and culture) conversion in patients receiving appropriate first-line or second-line TB treatment (4, 6, 7, 25). Experts have suggested that reduction in infectiousness occurs much earlier than culture or smear conversion – possibly as early 2–3 days after the initiation of effective TB treatment among patients with drug-susceptible TB (DS-TB) and 2 weeks after effective TB treatment among patients with DR-TB.

Implementation considerations

National TB programmes (NTPs) should ensure prompt initiation of TB treatment after diagnosis (4, 25). Access to WHO-recommended rapid tests (e.g. Xpert® MTB/Rif or Truenat TB assay) paves the way for earlier detection and prompt start of treatment (25). If rifampicin resistance is detected (4), access to rapid testing for resistance to second-line drugs and phenotypic DST should also be ensured so that the treatment can be tailored to the resistance pattern. NTPs should also extend support (e.g. for treatment adherence and linkage to social protection schemes to prevent financial hardship, nutritional support and health education to patients and their families) to increase the likelihood that treatment is completed. All these measures help to render the patient noninfectious as early as possible.

Box 2.2. FAST: an approach for rapid detection, separation and early start of TB treatment (26)

TB patients who are undiagnosed and are not being treated present a particular risk for transmission of TB. Undiagnosed TB patients may be in clinics, waiting areas, hospital emergency rooms or wards for general medical or other clinical services. Asking all those seeking care at a health care facility about TB symptoms can help to diagnose previously undetected TB. Prompt collection of a sputum specimen for a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic test, and clinical evaluation with chest X-ray can speed up diagnosis. Patients diagnosed with TB or multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) should be triaged to a well-ventilated area to prevent transmission to other patients, and treatment should be started as soon as possible, to reduce the duration of infectiousness. FAST is an approach that focuses on finding TB cases actively, separating safely and treating effectively (26). The FAST strategy builds on a renewed appreciation that effective TB treatment rapidly reduces the spread of TB spread, even before the sputum smear and culture turn negative. FAST aims to triage individuals with respiratory symptoms, use rapid diagnostics to identify M. tuberculosis, undertake DST, and immediately start effective TB treatment and monitoring.

Source: Nardell (2019) (26).

2.2.4 Respiratory hygiene

Evidence

Respiratory hygiene (or hygiene measures) is defined as the practice of covering the mouth and nose during breathing, coughing or sneezing to reduce the dispersal of airborne respiratory secretions that may contain M. tuberculosis bacilli; for example, by wearing a respirator, a medical mask or a cloth mask, or covering the mouth with a tissue, sleeve, or flexed elbow or hand, followed by hand hygiene (6, 7, 13). Respiratory hygiene (including cough etiquette) is a key measure for interrupting transmission. Although there is literature on the dynamics of cough aerosols containing M. tuberculosis, data to compare the effectiveness of different respiratory hygiene manoeuvres are scarce.

Only five relevant studies were identified through a systematic review of evidence ahead of the latest update of the WHO guidelines (13). Meta-analysis was not possible because of significant differences between the intervention and study populations. Despite the low certainty of the evidence, the GDG deemed the recommendation for respiratory hygiene to be strong, given its potential for preventing a life-threatening or catastrophic situation, which could occur if health care workers or other contacts were to develop TB infection and progress to TB disease. The GDG stressed that the use of this measure as part of a package of interventions can help to reduce TB transmission. One of the studies included reported a reduction of 4.1–12.4 tuberculin skin test (TST) conversions per 1000 person-months among health care workers when surgical mask were used by patients until isolated (alongside other TB IPC interventions). Another study reported a reduction of about 15% in risk of incident TB infections among health care workers when people with presumed or confirmed TB used surgical masks. However, the effect of wearing a medical mask in reducing incidence of TB disease is modest or absent.

Implementation considerations

Respiratory hygiene measures should be promoted among individuals with confirmed or presumed TB in all health care settings, and in other settings where the risk of transmission is high (e.g. in households and nonhealth care congregate settings). These measures should be brought in regardless of the burden of TB disease in the given country, setting or community, and regardless of the level of the health care facility (primary, secondary or tertiary). Places where it is particularly important to promote such measures include consultation rooms, inpatient facilities, and the waiting areas in health facilities. Areas to be considered for programmatic implementation of respiratory hygiene include the following:

- Health education on respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette for health care workers, patients and community members

- Counselling on respiratory hygiene for TB patients and their families, as part of a comprehensive package of TB care.

- Efforts to mainstream respiratory hygiene practices or cough etiquette as standard practice for all individuals with a cough in the health facilities or congregate settings, not just at TB facilities. Such efforts will also help to alleviate the social stigma associated with TB.

- Provision of disposable handkerchiefs and medical masks to all symptomatic individuals. All such individuals should be instructed to cover their mouths until TB is ruled out.

- When designing guidelines, protocols and SOPs for children with TB, it is important to note that children are generally paucibacillary and contribute much less to M. tuberculosis transmission, and that those with severe illness may have difficulty in breathing when masked.

- Consideration that the implementation of respiratory hygiene activity at health facilities and in congregate settings using medical masks requires additional funds, and adequate reflection of this situation in annual health facility IPC plans and budgets.

- Consideration that medical masks are a standard item for procurement at health care facilities, along with other medical supplies. Enough medical masks should be procured to cater for all patients with a cough visiting the health facility, all patients diagnosed with TB and all accompanying visitors. Supply problems are sometimes encountered in congregate settings because medical masks may not be a standard item for procurement; TB programme managers should advocate with the authorities at such facilities to ensure that a budget is allocated for procurement of medical masks

- Signage can be an effective way of educating patients, visitors and staff, and of reinforcing key messages. All waiting areas in the facility should display posters or banners in local languages with simple messages. The signage should promote cough etiquette and knowledge of the signs and symptoms of TB and should explain that TB is both preventable and curable.

2.3 Staff training and education on TB IPC

2.3.1 TB prevention among health care workers

Health care workers are at increased risk of acquiring TB infection and disease when IPC measures are not effective. These workers have the right to work in a safe environment, and a professional obligation to act in a way that minimizes the risk of harm to those under their care (24). Governments and programmes should therefore strengthen measures to reduce these risks, as follows:

- uninterrupted access to PPE, including appropriately fitting respirators, should be ensured for health care workers, particularly those engaged in TB patient care;

- all health care workers should receive appropriate information and rapid TB diagnostic testing if they have signs and symptoms suggestive of TB (27);

- all health care workers (including those newly recruited) and other staff engaged in direct patient care should receive periodic screening for TB symptoms, chest X-rays and testing for TB infection (2);

- based on the results of the evaluation, health care workers should receive, free of charge, either TPT (preferably a shorter rifamycin-containing TPT) or a full course of TB treatment;

- all health care workers should be given information about HIV and access to HIV testing and counselling (27) – if diagnosed with HIV, they should be offered a package of HIV prevention, treatment and care that includes regular screening for TB disease and access to ART and TPT;

- HIV-positive health care workers should not be allocated to posts involving care of patients with known or presumed TB or DR-TB; instead, they should be offered positions where exposure to untreated TB is low; and

- if found to have TB disease, health care workers should be notified to the NTP and linked to any other benefits (e.g. paid leave and illness allowance), as per the country’s national occupational health policy

Annex 4 provides a template for routine TB screening among health care workers and Annex 5 provides an example of a register that can be used to record screening and treatment progress.

2.3.2 Training of staff

Training and continuing education are key to the successful implementation of administrative controls and other aspects of IPC. All health care and other personnel working in the facility – whether clinical, laboratory, maintenance, office or other staff and volunteers who routinely work in the facility – must receive TB IPC training. In a large institution, clinical and nonclinical staff may be trained separately, to allow for open dialogue and free discussion on ways to strengthen TB IPC. The training and education should aim to cover the following areas:

- M. tuberculosis and how TB bacilli cause infection and disease, and the differences between the infection and the disease;

- transmission and acquisition of TB (e.g. through coughing, sneezing, speaking or ingestion);

- signs and symptoms of TB disease;

- how overcrowding and other environmental factors affect TB transmission;

- how environmental controls can reduce the risk of transmission in health facilities or congregate settings;

- how and when to use appropriate respiratory protection such as respirators and medical masks;

- fit-testing and seal checks (Fig. 4.1), and how to store and dispose of used respirators and medical masks;

- information on the availability and effectiveness of treatment for both TB disease and TB infection, and communication of the fact that shorter regimens with improved safety profiles are now available for the treatment of DS-TB, DR-TB and TB infection; and

- the importance of screening all individuals with signs and symptoms of TB using appropriate referrals, including access to chest X-ray, tests for TB infection and linkage with TB treatment or TPT.

Box 2.3 summarizes suggested content on triage that may be covered during training, sensitization or review meetings involving staff and volunteers. This content may be used to develop a standard questionnaire and checklist to assist health care workers in performing triage (28, 29).

Box 2.3. Key content for training and sensitization on triage

- Why triage? Principles underlying triage and practical aspects of its organization.

- Steps to take once individuals with signs and symptoms suggestive of TB are identified:

- education on cough etiquette;

- promotion of the use of medical masks;

- respiratory separation and evaluation for TB; and

- prompt TB treatment if TB disease is detected.

- Personal protection for health workers and staff:

- education on how to wear a particulate respirator correctly;

- the importance of continued use of masks or respirators;

- how to avoid contamination during use, removal and disposal of medical masks and respirators; and

- when to change the medical mask or respirator (e.g. when it gets wet or dirty with secretions).

Source: Visca et al. (2021) (28); TB/COVID-19 Global Study Group (2021) (29).

2.3.3 Education of patients and visitors

In addition to regular training and sensitization of staff and volunteers, the IPC committee and the staff in charge of the facility should ensure that culturally appropriate education material and messages are available in the local language, to educate patients and visitors. Such education material should be used in signage, brochures, posters or videos displayed in waiting areas or offered through individual or group education sessions by trained facility staff. The following are template messages that may be developed to suit the local context:

- TB spreads through the air when an infectious TB patient coughs, sneezes or sings;

- if you have a cough, you need to have it investigated with a sputum examination, chest X-ray or other investigation advised by health workers;

- cover your mouth and nose with a tissue or clean handkerchief when you cough or sneeze – in the absence of a handkerchief or tissue, cough or sneeze into your elbow;

- follow cough etiquette and do not spit indiscriminately; collect sputum in a dedicated container and learn how to dispose of it safely when at home;

- sleep in a well-ventilated room, preferably with cross-ventilation; ensure your other rooms are also well ventilated;

- do not travel to or visit congregate settings if you have a cough or if TB is diagnosed;

- if TB is diagnosed:

- start treatment immediately and complete it as advised by health workers;

- encourage your close contacts and people in your household to take up TPT; and

- ensure you adhere to your treatment plan – regular uninterrupted TB treatment is critical to reduce transmission of TB to family members and contacts and for you to get cured.

Fig. 2.3. Examples of education sessions on TB IPC for visitors and health care workers in health facilities

Source: US CDC (2022) (30).

Annex 6 provides examples of education materials that can be developed for different stakeholders. These can be tailored to the local context and adapted for use at health facilities. Box 2.4 describes how a TB IPC toolkit was implemented in Nigeria and Box 2.5 describes how the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) in India, implemented TB IPC interventions.

Box 2.4. Country experience – implementing a TB IPC toolkit in Nigeria

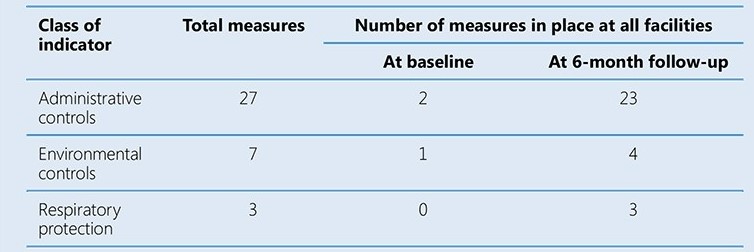

In 2015, the TB BASICS toolkit, developed by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), was piloted in Nigeria. The pilot implementation was done in collaboration with the MoH at seven facilities across three states that collectively served a population of 1.48 million, including about 1600 TB patients, at the time of the pilot. The intervention comprised four steps: training of health care workers, baseline assessment, implementation of changes to fill the gaps, and follow-up assessments.

About 50 health care workers received a 3-day training of trainers on the TB IPC toolkit. Knowledge gaps were identified, and education materials were provided for dissemination to other staff. The baseline assessment included interviews, direct observation of activities and policy review. Assessment teams were made up of MoH staff from the state, regional and national levels; representatives from the implementing partners (CDC, WHO and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief [PEPFAR]); health care providers from the selected facilities; and residents from the Nigeria Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program (NFELTP).

The assessment teams noted particularly large gaps in the implementation of administrative controls. Sites received feedback, which was used to develop facility-specific plans. Interventions that did not require additional funds were implemented immediately, followed by the acquisition of posters, pamphlets and supplies such as PPEs. Renovations were done as required and an occupational health programme was implemented. Three follow-up assessments were conducted at 2-month intervals by NFELTP residents, with the full assessment team joining for the final evaluation. The table below summarizes the results at baseline and at the final 6-month follow-up.

In addition to the marked improvement in the number of IPC measures implemented, three cases of TB among health care workers were detected, about 200 health care workers were trained. The pilot study helped to build local capacity to implement and monitor TB IPC interventions

Source: Dokubo et al. (2016) (31).

Box 2.5. Country experience – evolution of TB IPC efforts in India

In India, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) has proactively implemented tuberculosis (TB) infection prevention and control (IPC) interventions since 2010, as part of the broader national airborne infection control (AIC) policy. Following the release of the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on TB IPC in 2009, the MoHFW established the National AIC Committee. The committee had a mandate to serve as a multi-speciality coordinating group to develop national AIC guidelines for India and provide guidance for their implementation, evaluation and revision. In 2010, national guidelines on AIC were developed, with support from WHO India (1). The committee recommended to undertake AIC baseline assessments and capacity building at 35 health facilities (from primary to tertiary level), in both the public and private sectors in three states, and to start pilot implementation (2). The National Institute of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases (NITRD), New Delhi, organized a national capacity-building workshop with technical support from WHO India and the United State Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC). In addition, PATH – an international, global health organization (USA) – supported capacity-building of architects and engineers and organized an experience-sharing workshop. During the pilot phase it became clear that the effective implementation of AIC policies and practices requires a combination of capacity-building and systems strengthening. Following the pilot phase, the implementation of TB IPC was prioritized in settings with a high risk of TB, such as multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) centres, TB culture laboratories and anti-retroviral therapy (ART) centres. TB IPC training was mandated for staff at these facilities. In 2014– 15, an AIC assessment was conducted at 30 ART and TB centres across five states. The assessment highlighted the need to strengthen implementation of TB IPC, and enhance resource allocation and the availability of trained staff to implement TB IPC (3).

In 2014, experts from US CDC and the Harvard School of Public Health provided training in engineering aspects of infection control. The training was given to faculty and staff at the Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College – a large medical college hospital in Mumbai – and to engineers and medical officers working with the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM). An assessment of MCGM health facilities was undertaken and various cadres of health workers were trained. In 2018, the US CDC and MCGM established an AIC unit to support TB IPC training, 4-monthly facility assessments and development of sitespecific AIC plans, including timelines and identification of those responsible for mitigating identified deficiencies. This support was later extended to all 24 administrative units in Mumbai.

In 2020, the MoHFW updated the national guidelines for IPC (4) and aligned the TB IPC section with the latest WHO recommendations (5). In addition, information and communication materials targeting community, health workers and the media were developed and were widely disseminated, including during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Since 2022, the MoHFW – with support from the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), WHO India, the US CDC and NITRD – has implemented independent AIC assessments, facility upgrades and training at more than 100 institutions with co-located centres for drugresistant TB, using the C19RM funding from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. The NTEP has also implemented a project (Germ-free TB IPC) that is supported by the US CDC and SHARE India at 60 facilities in 10 states. The project developed and tested mentorship models, training content, toolkits and awareness materials for capacity-building of health care workers.

The MoHFW India considers TB IPC to be an integral component of the prevention pillar of the national TB strategic plan, along with TB preventive treatment (TPT) and, in the future, evidence-based adult TB vaccination to end TB. In additions at subnational level, states are taking innovative action to implement TB IPC measures, such as establishment of “cough corners” in health facilities to educate, segregate and fast-track symptomatic individuals, and distribute AIC kits along with education materials to the patients and visitors (e.g. Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh and Kerala).

References for Box 2.5

1. Guidelines on airborne infection control in healthcare and other settings. New Delhi: Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; 2010 (https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/4830321476Guidelines_ on_Airborne_Infection_Control_April2010Provisional.pdf)

2. Parmar MM, Sachdeva K, Rade K, Ghedia M, Bansal A, Nagaraja SB et al. Airborne infection control in India: baseline assessment of health facilities. Indian J Tuberc. 2015;62:211–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtb.2015.11.006.

3. Sachdeva K, Deshmukh R, Seguy N, Nair S, Rewari B, Ramchandran R et al. Tuberculosis infection control measures at health care facilities offering HIV and tuberculosis services in India: A baseline assessment. Indian J Tuberc. 2018;65:280– 4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtb.2018.04.004.

4. National guidelines for infection prevention and control in healthcare facilities. New Delhi: Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; 2020 (https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/National%20Guidelines%20for%20 IPC%20in%20HCF%20-%20final%281%29.pdf).

5. WHO guidelines on tuberculosis infection prevention and control, 2019 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311259).

Обратная связь

Обратная связь